Can Moderation Help Multi-LLM Cooperation?

What happens when you add a neutral moderator to help LLMs cooperate in strategic games? Spoiler: it works way better than you'd think.

Large Language Models are pretty good at optimizing for themselves. But when you put multiple LLMs in a strategic game together, things get messy. They can optimize for individual benefit, but they struggle with cooperation and fairness when incentives don't align (Akata et al., 2023).

Think about it: if you're playing a game where you can either cooperate or defect, and defecting gives you a better individual outcome, why would you cooperate? That's the classic Prisoner's Dilemma problem. But here's the thing: cooperation and fairness are crucial in multi-agent scenarios.We're moving toward a future where multi-agent systems interact with humans to perform tasks or negotiate as representatives, making cooperation a crucial design objective.

So my collaborators Harshvardhan Agarwal, Pranava Singhal, and I asked: what if we introduce a neutral LLM moderator to help agents cooperate? Can a third-party agent guide LLMs toward mutually beneficial strategies, especially when individual incentives are misaligned with cooperative ones?

The Research Questions

We set out to answer two main questions:

- RQ1: Does a moderator lead to better cooperation and fairness in outcomes? We formalize fairness using game theory concepts like social optimum (maximizing the minimum utility across all agents).

- RQ2: Do agents have a better perception of each other in a moderated conversation?We measure this through social skills like trustworthiness, cooperation, communication skills, respect, and consistency.

Background and Motivation

The behavioral patterns of LLMs can be effectively studied by constructing game scenarios with different incentive structures and analyzing their choices through game theory. This gives us a mathematical framework to understand when and why cooperation breaks down.

Game Theory Basics

In a normal/strategic form game, N players simultaneously choose from action sets. Each player's outcome is determined by a utility function.The simultaneity of choice is crucial since each player acts without knowing others' actions.

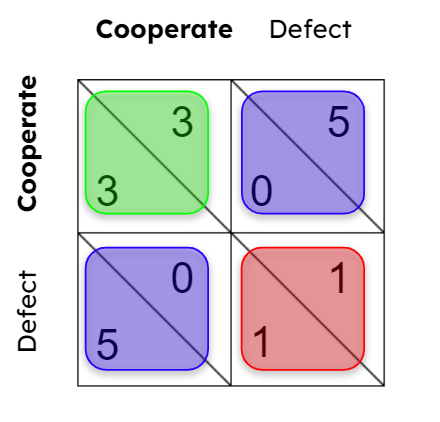

For the simplest case, two players each have two actions. Their utilities are represented in a2 × 2 matrix where entry(i, j) shows the payoffs for both players.

There are three key concepts we care about:

Nash Equilibrium

A strategy profile where no player can gain by unilaterally changing their strategy while others remain fixed. Multiple Nash equilibria can exist, but they may lead to suboptimal outcomes.

Pareto Efficiency

A state where it's impossible to improve one player's outcome without making another worse off(Lewis et al., 2017). While commonly used in negotiations, Pareto efficient strategies may differ from Nash equilibria.

Social Optimum

The strategy profile that maximizes the minimum utility across all agents, representing the fairest outcome. By definition, it is Pareto efficient. This is what we're trying to achieve.

Why We Need a Moderator

Why is it so difficult to achieve cooperative and fair outcomes? If an agent stands to improve their reward by unilaterally changing their strategy, they will do so unless there's an incentive to play fair. In game theory, cooperation is achieved through two key means: enforcing contracts with additional penalties/rewards, or trust and mutual agreement between agents.

The second approach is particularly effective since both agents stand to lose if the other agent mistrusts them. This is especially seen in LLMs playing multi-turn games where an agent taking an unfavorable action once causes the other agent to never cooperate again (Akata et al., 2023).

Key Insight

If both agents cooperate, they can potentially maximize their cumulative reward over multiple turns, making the social optimum and fairness suitable objectives for multi-agent strategy and negotiation. A neutral moderator can foster trust and emphasize long-term consequences, reducing agents' incentives to deviate from the social optimum.

Methods

We designed experiments to test whether a moderator improves cooperation across diverse game settings. We use game theory-based payoff matrices to get comprehensive coverage of different utility structures.

Synthetic Game Setting

We tested five classic game types: Prisoner's Dilemma, Hawk-Dove, Stag Hunt, Battle of the Sexes, and Deadlock. These games cover diverse incentive structures where Nash equilibrium and social optimum sometimes align and sometimes don't.

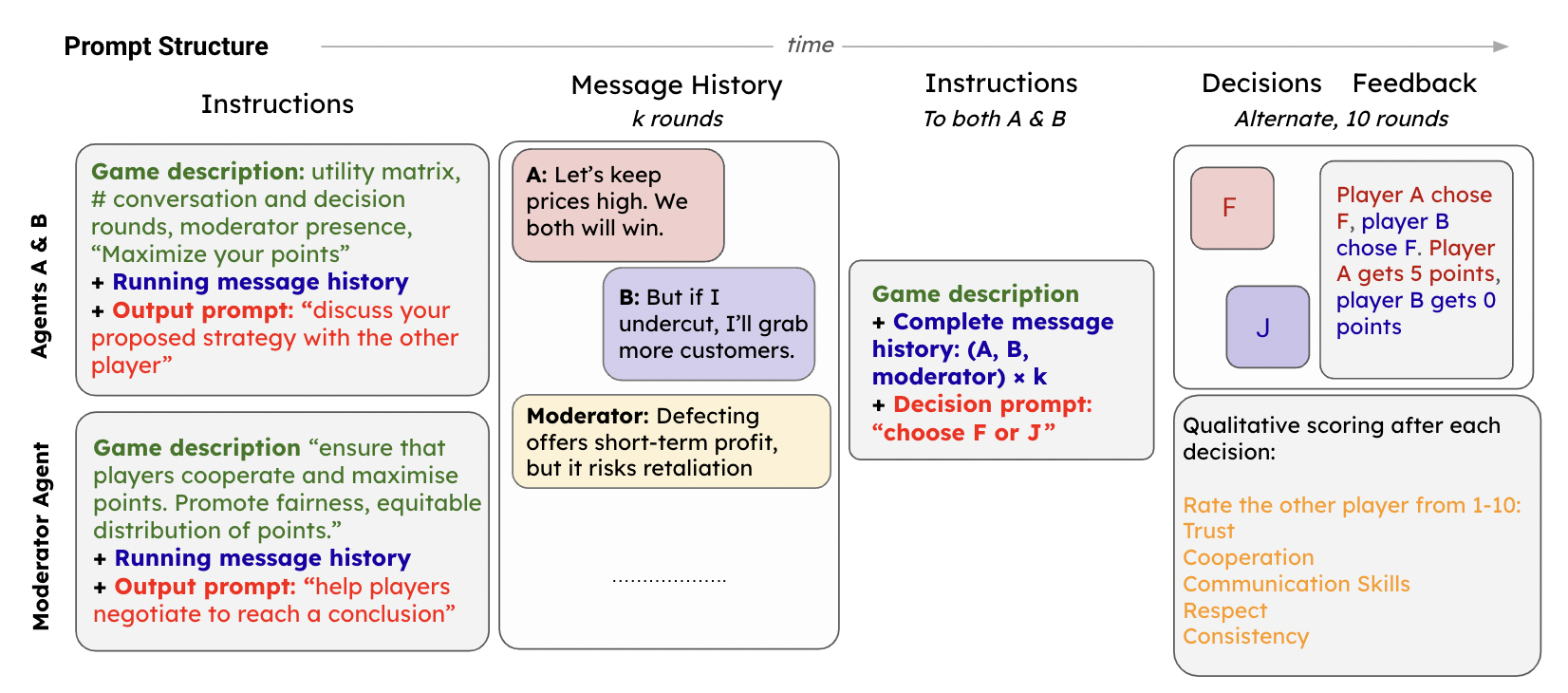

The experiment has two main stages:

- Conversation Rounds: Agents are prompted with the game setting (utility matrix), contextual information, and instructions to converse. In moderated sessions, a moderator agent is included, explicitly tasked with promoting fairness and social optimum outcomes. Agents converse for

krounds. - Decision Rounds: After conversation, agents independently make decisions labeled "F" and "J" (to avoid textual bias). Decisions are made iteratively over 10 rounds, with each agent's choice revealed after each turn. Agents also qualitatively rate each other based on trust, cooperation, communication, respect, and consistency.

Realistic Game Setting

Existing works specify utility matrices explicitly in prompts, which is unrealistic. We created theRealisticGames2x2 dataset with 100 unique game settings that capture real-world scenarios like military arms races, office resource allocation, and environmental conservation efforts.

This dataset reflects real-world conditions with imperfect information and qualitative/relative ordering of outcomes, making it more applicable than synthetic matrices alone.

Evaluation Metrics

We define the total utility for player P_i overT turns as:

UP_i = Σk=1T UP_i(k)The social optimum objective maximizes both total scores and minimizes the difference between players:

U* = 2 min(UP_1, UP_2) = (UP_1 + UP_2) - |UP_1 - UP_2|We also measure qualitative factors: Trust (T), Cooperation (C), Communication Skills (CS), Respect (R), and Consistency (S), each scored 1-10.

Results

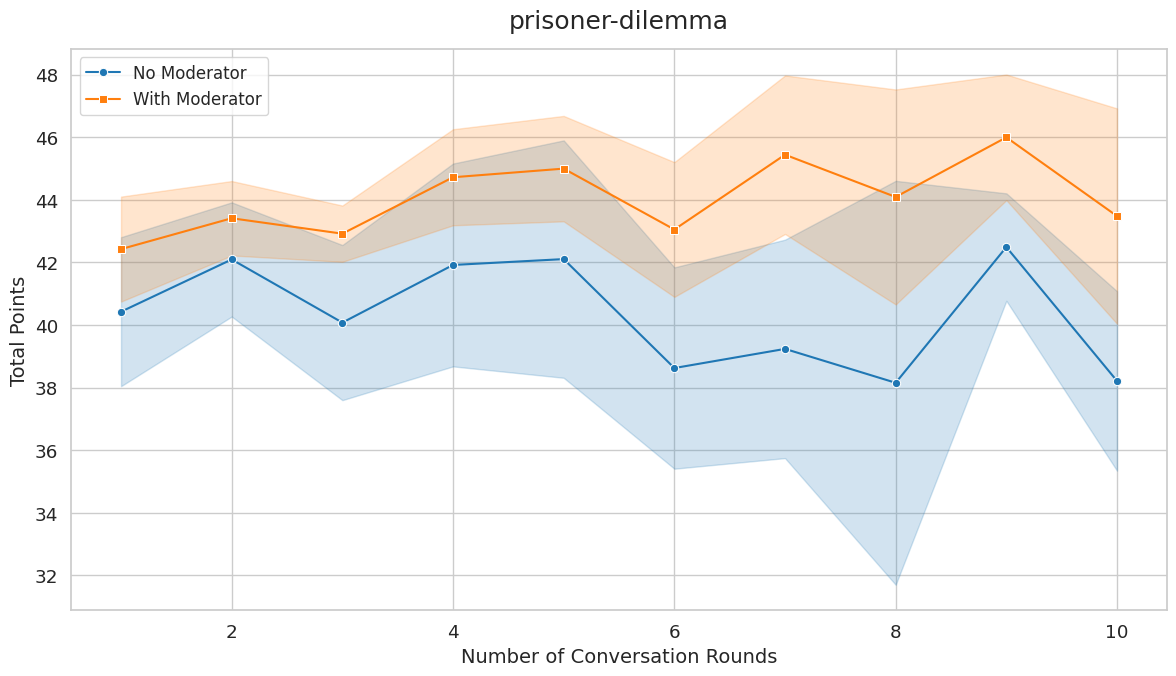

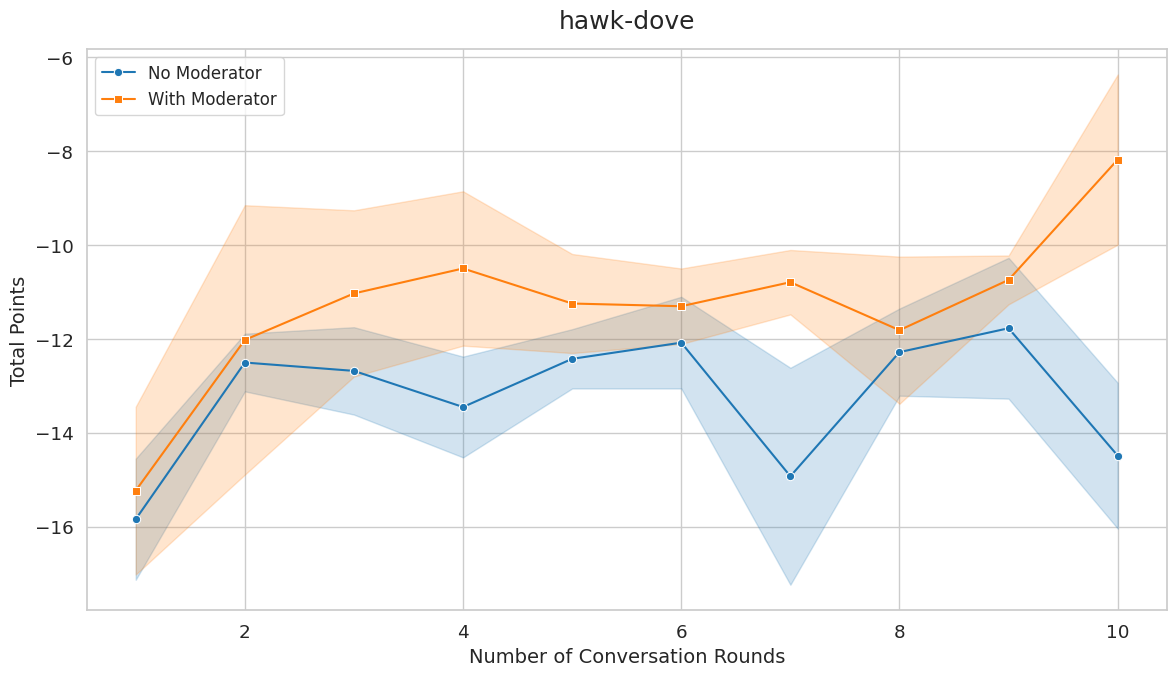

All experiments used LLaMA 3.2 3B and results are averaged over 4 seeds to account for noise.

Synthetic Game Results

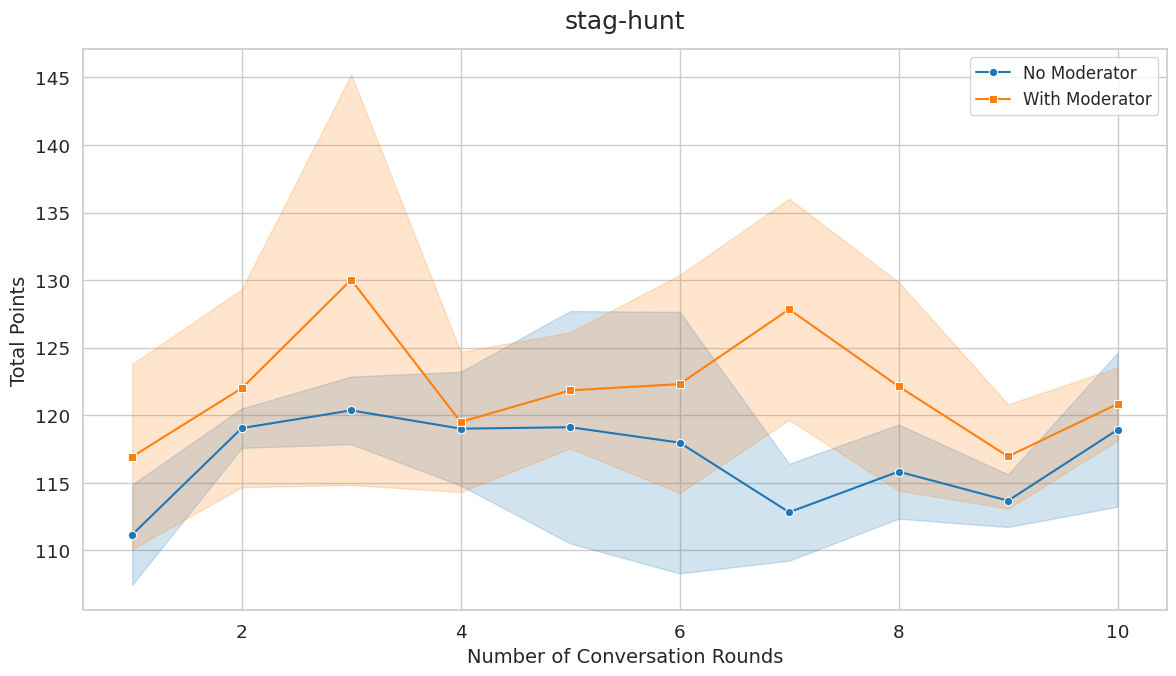

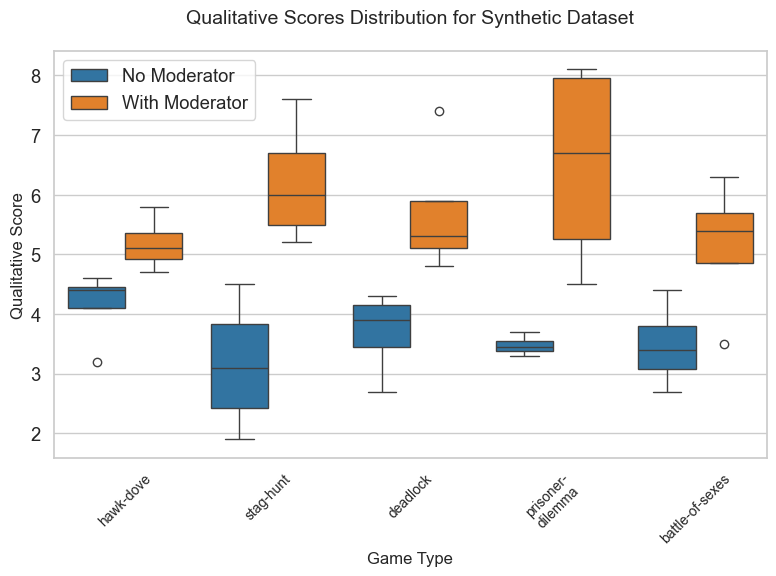

First key finding: In game scenarios where the Nash equilibrium is distinct from the social optimum, our moderator consistently improves fairness and cooperation. This includes Prisoner's Dilemma, Hawk-Dove, and Stag Hunt.

Second key finding: In games where the Nash equilibrium coincides with the social optimum (Battle of the Sexes, Deadlock), the moderator doesn't significantly improve outcomes. This makes sense: agents are already individually driven toward the social optimum, so moderation can't help much.

These results indicate that moderation plays a critical role in fostering cooperative strategies when individual rationality conflicts with collective benefit. The moderator effectively provides a neutral perspective that reminds agents of the collective benefit of cooperation and encourages trust.

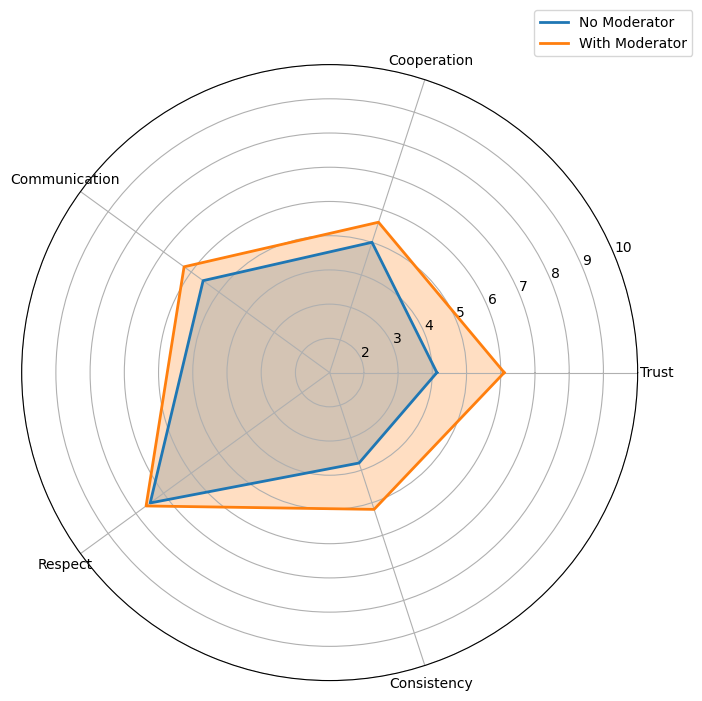

Our qualitative results show consistent improvement in agents' perception of each other across all parameters (trust, cooperation, communication, respect, consistency) when a moderator is present. This addresses our second research question: yes, agents do have a better perception of each other in moderated conversations.

Realistic Game Results

As expected, it's more challenging for LLM agents to perform well in realistic game settings where utility matrices aren't explicitly provided. Moderation generally improves scores in realistic settings, except for Battle of the Sexes (which requires coordination across turns, something our current setup doesn't fully support).

The difference is relatively limited since real-world scenarios don't have explicit payoff matrices, making it a harder problem for LLMs. But the trend is clear: moderation helps.

Deal or No Deal Results

We also tested on the Deal or No Deal dataset (Lewis et al., 2017), where agents split an inventory of items (books, hats, balls) with different values.

Most conversations resulted in either disagreements or invalid item counts, leading to zero scores. There was no significant quantitative difference with a moderator. However, qualitative metrics showed consistent enhancements, with the most substantial improvement in trust.

Discussion & Future Work

This study demonstrates that LLM-based moderators can improve cooperation and fairness in multi-agent games, especially when individual incentives conflict with collective benefit. The development of theRealisticGames2x2 dataset also provides a valuable resource for investigating LLM behavior in strategic interactions.

Limitations: Our setup focuses on two-player, two-action games. Expanding to more complex games (multi-player, extensive-form, partial information) remains an open challenge. Additionally, attempts to train the moderator using PPO were unsuccessful due to training instability from the probabilistic reward model.

Future Work: Extending to more complex game-theoretic settings, improving moderator training with alternative methodologies, and investigating whether improvements in fairness are uniformly distributed across demographic groups are all promising directions.

References & Resources

Papers & Resources:

- Akata et al. (2023) - Playing repeated games with Large Language Models

- Lewis et al. (2017) - Deal or No Deal? End-to-End Learning of Negotiation Dialogues

- Abdelnabi et al. (2023) - LLM-Deliberation: Evaluating LLMs with Interactive Multi-Agent Negotiation Games

- Costarelli et al. (2024) - GameBench: Evaluating Strategic Reasoning Abilities of LLM Agents

- Bakhtin et al. (2022) - Human-level play in the game of Diplomacy

- Gandhi et al. (2023) - Strategic Reasoning with Language Models

Code & Dataset:

This work was done with Harshvardhan Agarwal and Pranava Singhal as part of CS329x at Stanford. All authors contributed equally to this work.